Your studying should be enjoyable, meaningful, and productive, so you can maximize your USMLE scores and impress residency programs. We want to answer any question that you have about the Course or how you should prepare. If you have anything you’re unsure of, please ask, we’ll answer!

I’ll update this page with responses. My goal is for you to know EXACTLY what you should be doing, every single day. If your question isn’t answered, then please post it as a comment here!

Table of Contents

You should ALWAYS do all of your old (due) cards every day. No exceptions.

For new cards, it will depend on how much time you have (i.e. are you studying full-time or are you in clerkships/classes?). Generally, I recommend 20-50 new cards/day.

Learn more about what daily minimums you should be doing every day here.

There are many, many reasons you may be struggling to do the daily minimums. See this page here on how to improve your minimums and accomplish more.

Here are the schedules I recommend for dedicated study, pre-dedicated study, or clerkships.

Generally speaking, Yousmle Online Course videos should take the place of mastering your own topics, especially in the beginning. For example, it is much harder to teach yourself heart failure using a QBank/First Aid than it would be to use the Online Course modules.

The best time to do videos would be late afternoon/evening, and reserve the morning/earlier peak study time for QBank and Anki.

Here are the schedules I recommend for dedicated study, pre-dedicated study, or clerkships.

Here is an article on how to best study on clerkships.

There are many reasons why it may be hard to do one or more of the minimums. The biggest is if you are taking classes/clerkships, or have a busy load generally.

We sympathize. It is hard to have more things that you want to do than there is time in the day. Especially if you believe “slow is fast,” it is hard to feel chronically playing catch-up.

Two solutions are the following:

You may be wondering, “wow, I seem really slow at doing/reviewing QBank questions, or Anki cards.” A smaller percentage of you may wonder if you are doing your reviews/learning too quickly. Both reviewing too fast and too slow can be problematic. Both have reasonable guidelines, depending on how strong/weak your foundation is.

Generally speaking, if you can do and review 10 QBank questions in an hour, that is a very reasonable pace. So is doing more questions/hour better? Not necessarily. If you are doing 20 questions an hour, that is either very good or, if your foundation is weak, that may even be a little too fast to actually understand the material in the questions itself. It all depends on how strong your foundation is and how much time you should be putting into strengthening it.

Everything is relative! Most people think that things take too long, only because they don’t have a reference point. But generally:

In other words, if you had 200 old cards to review, and wanted to do 60 QBank questions and review them, you might expect ~8 hours of actual studying. Much more or much less than that (swings of more than 50-100%, so > 200 cards/hour, or > 15-20 QBank questions/minute) may mean that you are moving too quickly and not learning the material well.

Note, however, these are rough guidelines and will vary, especially on the extremes of foundation. If your foundation is strong – and you’ll know this if you’re getting > 75% of QBank questions correct or have NBMEs > 230 – then doing more than 15-20 QBank questions/hour may be reasonable, especially if they are on topics you already know well. However, if your foundation is particularly weak – QBank percentages < 50%, or NBMEs < 170 – you may need to take a bit extra time. Doing QBank questions or Anki cards too quickly may actually retard your progress. Remember, the worst studying you can do is the studying you’ll have to repeat.

Generally, you should beware of rushing, as it will almost always lead you to take more time. A favorite story of mine goes something like this:

This story illustrates the importance of not rushing. There are numerous reasons why rushing makes you less efficient. One of the biggest reasons: by rushing, you have to re-do your work.

A favorite phrase of a former PI of mine was, “slow is fast.”

If you’re pressed for time and want the briefest of quick-start guides, these are the lessons I’d recommend starting with:

Your goals when you start the Online Course are these:

Remember, the best studying is the learning you don’t have to repeat. Set a goal of mastering as much material as you can every day, and you’re well on your way to USMLE (and career) success.

You can read more on the best way to not rush here.

The tendency to rush is enormous, especially as your exam approaches. Our entire lives we have been encouraged to rush. Grades in high school were largely based on short-term assignments/mid-terms. Rarely did we have exams that tested us on our long-term recall or ability to use knowledge. Rather, we had a series of tasks that encouraged short-termism and cramming.

Even if we knew that cramming was bad, there wasn’t a ton of encouragement to think about the long-term. Our cramming/short-term behavior was logical.

As depressing as it is for me to contemplate, in many ways our education system encourages short-term thinking over long-term retention. The good news? You’ve entered a field (medicine) where your long-term retention and ability to apply information will show up in your exams. Thinking about the long-term – rather than your next mid-term – is rewarded with higher scores on comprehensive exams like the USMLEs. More importantly, thinking long-term positively impacts your ability to help patients. (Who wants a doctor who crammed their way through med school?)

But so far, this doesn’t address your issue – you have only a few weeks/months before your test, and you feel panicked. You know you have way too much to do, and too little time, and the only path you can see is to try and cram more tasks into a shorter period.

Let me explain why rushing will be a mistake.

Unlike crammable med school exams, the USMLEs test your ability to apply information. They state this clearly in the guidelines they give to all the question-writers. In other words, you cannot memorize your way to higher USMLE or shelf scores. Rather, you must master the information.

If you believe the premise that you must master information to use it well and get more USMLE questions right, ask yourself this: if you rush, how well will you master the information? The unfortunate answer is that by rushing, even though you “cover” more, you will, in fact, be able to apply less.

The solution is to master the information, which will feel slow, but it is, in fact, faster. It is faster to master a smaller amount of information every day because by mastering it, you won’t have to re-study it. Remember, the worst thing you can do is to “cover” something so quickly you have to study it again.

In psychology, there is a term called the “paradox of hedonism.” The observation is that if we seek a particular pleasure, we will fail to achieve it. (E.g., those who seek only to be happy are, paradoxically, less happy).

Other prominent thinkers have echoed similar ideas, including CS Lewis who once said that if you aim for attaining earth (e.g., worldly pleasures), you would attain neither heaven or earth. But if you aim for heaven, you will attain it, and have earth thrown in as a bonus.

I’ve found a variation to be true for studying, which you could call the “paradox of speed.” If you seek to move quickly (e.g., quickly doing lots of QBank questions or watching lots of videos, etc.), you will achieve neither speed or quality. This is because by seeking to do lots of QBank questions/videos/etc. you cannot achieve quality, and because you can’t achieve quality, you will not achieve a meaningful pace given the necessity to repeat your studying later.

However, if you seek quality (to take the initially slower process of mastery rather than cramming) you will paradoxically achieve a much greater speed, as well.

Deep down, you likely know rushing causes you to move slower and accomplish less. How often have you crammed something, only to have to return later to re-study the same thing? Or tried to quickly skim a QBank question, only to have to spend more time than normal on it because you had to re-read it so many times? Moving quickly may give you the illusion of speed, but it is the most inefficient and slow path.

Does this mean that you will “cover” less material, if you have to move slowly enough to master it? Honestly, no; like I said, paradoxically you will cover MORE meaningful material since what you master you won’t have to repeat. However, it will certainly FEEL like you are covering less, especially less than your friends that claim to have done all of First Aid in a matter of weeks.

The side-benefit of moving slowly enough for mastery is that if something unforeseen happens like your test is cancelled/moved back, you can only benefit. Why? Because all you have to do is to continue your slow path of mastery. As long as you’ve been making excellent Anki cards, following with the Course, and keeping up with daily minimums, all you have to do is keep studying your next weakest topics. Your mastery – and score – can continue to climb.

Contrast this with crammers who “cover” all of First Aid in the month before their test. They are operating under the fragile assumption that their test will happen in a month, and are aiming to have their knowledge peak at that month point. But what if their test is delayed, either because they underestimated how long it would take (so common this is called the “planning fallacy” in psychology) or it was canceled? They are screwed, because everything they’ve been cramming is leaking out of their head so fast that they won’t know what to do.

My advice? Act as if you have years to study, and the knowledge you are learning now you will need years from now. Not only will you continue to build the kind of baseline necessary to be an excellent physician, but you will likely paradoxically end up with even better scores than if you rushed/crammed.

If you still feel an intense pressure to move quickly, I’d recommend considering to delay your test, sooner rather than later. Knowing that you have 2-3 months to study will improve the quality of your studying dramatically, and as we discussed, likely cause your studying to take less time.

Sadly, most people don’t take enough time. They say, “well, I’ll see what happens in a month.” But because they are rushing, their score doesn’t improve, at which point they delay for another month to “see what happens.” Because they keep rushing, their scores still stagnate and they then delay for a third month. Paradoxically, due to all the rushing, they end up with much less accomplished than if they’d taken 2-3 months to study from the outset.

For more on why people vastly underestimate how long they should be studying, see this article.

Learning any valuable skill takes time. In the beginning, that skill, even if it ultimately causes you to go faster, will cause you to move slower. This is like the paradox of expediency that we discussed above.

Take, for example, walking. Most children crawl long before they walk. By the time they walk, crawling is a well-worn routine, and quite fast. So when they start walking, which do you think is faster – crawling or walking? Of course, crawling!! So, because walking is so slow, should they continue to crawl their entire lives?

Of course not. In the same way, question interpretation will take you a while to learn, and necessarily cause you to slow down in the beginning. You will review fewer questions than you could before (although you should find that you get a lot more out of them). However, you will find that the more material you master – and the more you hone your QI skills – the less timing on questions will be an issue. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that “timing issues” are in fact almost never timing issues, but in fact issues of weak foundation/QI.

If you’re not finishing blocks in enough time, you don’t need to work on timing. Instead, you need to master more material, make more concepts/intuitions automatic with effective pathophysiologic chronology Anki cards, and improve your interpretation skills.

We at Yousmle recommend a graduated learning curve for learning question interpretation.

This is a great question, one that usually comes from people who are often against a hard deadline (or something that FEELS like a hard deadline). We’ve all been there. We’ve fallen behind in some way. We see something that we wish that we’d started doing months/years ago like question interpretation. But our test is SOON. What do we do?

They say that the best time to plant a tree was 10 years ago. The second best time? Today.

In other words, for something that we should have been doing all along but haven’t, the response isn’t to keep cramming/avoiding a better approach. The best approach is to start working on that better thing IMMEDIATELY.

That said, let’s be practical. If you have 1-2 weeks before your test, you probably don’t have time to go through every single video on question interpretation. Instead, I’d focus on two things:

People who feel rushed often feel rushed in all aspects of their studying, which includes when they’re doing question themselves. They think that their struggles with “timing” on the test are due to the fact they’re not reading fast enough – so they read faster! Words and concepts blur together. As each block progresses, a growing sense of uneasiness and dread build.

Sound familiar? In my experience, issues of “timing” are in fact issues of foundation. If you struggle to make sense of a pathophysiologic chronology / scenario in the moment, it’s not because you’re reading too slowly. Instead, it’s because you never took the time to solidify that concept to begin with.

Slow down, both when you’re reading the question, and when you make the pathophysiologic chronologies. You’ll “cover” fewer questions, but you’ll never forget those things.

Remember, slow is fast.

A lot of people have asked my thoughts on various QBanks.

Step 1:

Step 2 CK/Shelf exams:

“Just do questions,” is common advice, but it often falls short. Generally, when you get a question wrong (or even right for the wrong reasons), it is either because you:

While it’s hard to give tailored advice without seeing you do questions, here are some lectures to help you on how to review/study UWorld or other QBank questions to get the most out of them:

https://course.yousmle.com/courses/learning-strategy/why-you-miss-questions

https://course.yousmle.com/courses/learning-strategy/why-youre-missing-questions-and-how-to-fix-it-2

https://www.yousmle.com/nail-fundamentals-usmle-step-1-nbme-practice-exams/

You may be wondering if you should make pathophysiologic chronologies for OLD questions that you’d done before you joined the Online Course. I typically don’t recommend it, since the act of DOING questions is quite useful. Making pathophysiologic chronologies is useful, however, it is most useful when done immediately after doing a question when everything is still fresh.

There is a balance when considering timed vs. untimed questions, tutor vs. test modes. From a learning standpoint, doing untimed, tutor questions is better. Virtually all forms of learning benefit from 1) the ability to focus without worrying about external things like timing, and 2) immediate feedback.

Think about training your dog not to chew the carpet. If your dog is chewing the carpet, you need to address the behavior immediately, not wait 4 hours until you take corrective action. Similarly, if you are making a mistake in reasoning – or lack a piece of knowledge – it is better to correct it immediately than wait 3 hours.

As such, when you are starting out, I highly recommend untimed, tutor mode questions so you can learn the process of question interpretation properly.

However, the real test is timed. It is a difficult transition to go from an untimed to a timed mode, NOT because doing untimed questions takes so long. Rather, it’s because we are so worried about the time that we speed up and HURT our timing. Often, even in untimed/tutor mode, you’ll find that the questions don’t take long. (Try it: time yourself!). Much of the struggle with timing is because:

Remember, each question is written such that you can read it, slowly, one time. Let me repeat: even for a slow reader like myself, I could read every question slowly, and still finish with plenty of time. When people struggle with timing, it is because they have to re-read questions.

To do question interpretation in a timed setting, you have to practice it timed. This is so you can prove you can read slowly and still answer all the questions. To that end, this is a schedule I recommend:

To read more about how to approach timing on USMLEs, read this article.

Generally, I favor mixed questions if you:

I’ll take these one by one.

If you’re scoring at least 10 points above passing, your foundation is likely strong enough that you don’t need to study (many) subjects by themselves. You might choose to study 2-3 systems individually, but you should be strong enough that you can cover things mixed.

On the other hand, if your score is below passing, you likely have a weaker foundation. To LEARN a subject that you are weak on, it is best to learn things from that system, as knowledge of one thing helps another. If I learn about MIs, it is easier to learn about heart failure. However, learning about CHF likely won’t help me learn about, say, microcytic anemias. If your foundation is demonstrably weak (e.g., your scores are below passing) then I would approach your first 3-5 systems individually.

The other major concern for learning is when presentations overlap. For example, presentations in cardiology, respiratory, and hematology often overlap. A 50-year-old man with chronic progressive dyspnea could be CHF, COPD, or anemia – you don’t know! However, if you are in the cardiology section, you’d guess CHF, which gives you an artificial advantage.

In contrast, for things like pediatrics, neurology, Ob-Gyn, psych, statistics, etc. you can likely study these without giving yourself an unnatural advantage. If a question starts with “A 23-year-old G1P0 comes to the physician for…” you know it’s an Ob question.

You may have noticed that question interpretation:

This is normal. Question interpretation requires focused attention. A reasonable amount of research (as well as lot of personal experience) shows that focused attention wanes the more we use it. So it is natural that our focus and ability to do question interpretation may wane as the number of questions increases.

How do we improve the quality and quantity of our focus so we can do quality QI throughout our entire exam?

First, you need to get good sleep. If you’re tired, the quality of your studying, including QI, will suffer.

Second, you need to make more of your QI automatic by making detailed pathophysiologic chronologies and doing them in Anki. (See this and this). When you’re starting out, you need to think about what every little sentence/detail means. However, over time, the more you make this thinking “automatic” by improving your intuitions, the less you’ll drain your pool of mental energy.

Finally, you might consider something like mindfulness meditation. There are a lot of putative benefits to studying. However, in my experience, mindfulness meditation itself is a skill that will hone your concentration. Rather than thinking of meditation as sitting in a room doing nothing, mindfulness teaches you to recognize when your mind wanders, and to bring it back to the present moment.

Sound like a useful skill for studying/taking tests? It is! I practiced mindfulness every day during my dedicated study, and it helped boost my concentration dramatically (and helped me sleep/lessened my anxiety). You can listen to the mindfulness body scan technique we used in a meditation class I organized at Stanford.

The most important thing that determines your score: the quality and consistency of your studying. Specifically, how well you are mastering, retaining, and applying the material. Spaced repetition has a huge impact on this.

The key distinction to make, especially when you’re starting out:

Let’s break this down into an algorithm for the different kind of cards you should make in different situations.

If you misunderstood the SAQ/what the point of the question was – this is often a skill deficit, and should be addressed by working on the skill, not by making more cards

A pathophysiologic chronology (PC) Anki card is meant to improve your intuition, and speed/accuracy of interpretations on your exam. If you haven’t made sense of something BEFORE your test, there is little chance of it making sense ON your test.

Making PC Anki cards will help you make crucial connections. Doing those cards will continue to reinforce those connections so they are fresh and automatic on your exams.

But a PC Anki card isn’t always appropriate. Let’s start by discussing when you should make a PC Anki card.

Remember, PC Anki cards help you to make connections, so that they are automatic by the time you get to your test. If you haven’t made sense of it before your exam, don’t expect it to suddely make sense during a pressure-filled test.

It’s a very simple 3-step process:

You can use these links to help you understand the process better. HINT: take your time with this. This is one of the most important skills you can learn, and most people do not get it right the first (or second) times.

https://course.yousmle.com/courses/question-interpretation/assignment-send-2-analyzed-nbme-questions-to-alec

As wonderful as PC Anki cards are, they can be long to make, and unnecessary in many circumstances. The biggest circumstance where you should NOT make a PC Anki card:

If you KNEW what every sentence meant, and could identify the SAQ, but simply didn’t know the answer to that stand-alone question → make a simple Anki card, like here

For example:

If you didn’t know that ketorolac was an NSAID, do NOT make a pathophysiologic chronology card on the pathophysiology of pre-renal injury to NSAIDS if you already knew the mechanism.

If you forgot the chromosome number for CFTR gene, but otherwise understand the pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis → do NOT make a pathophysiologic chronology card (a simple, fact-based card will suffice!)

You should NOT plan on taking every single NBME before your test. Why? Because if you end up needing to delay – or your test is canceled/postponed – you will regret not having a practice test available.

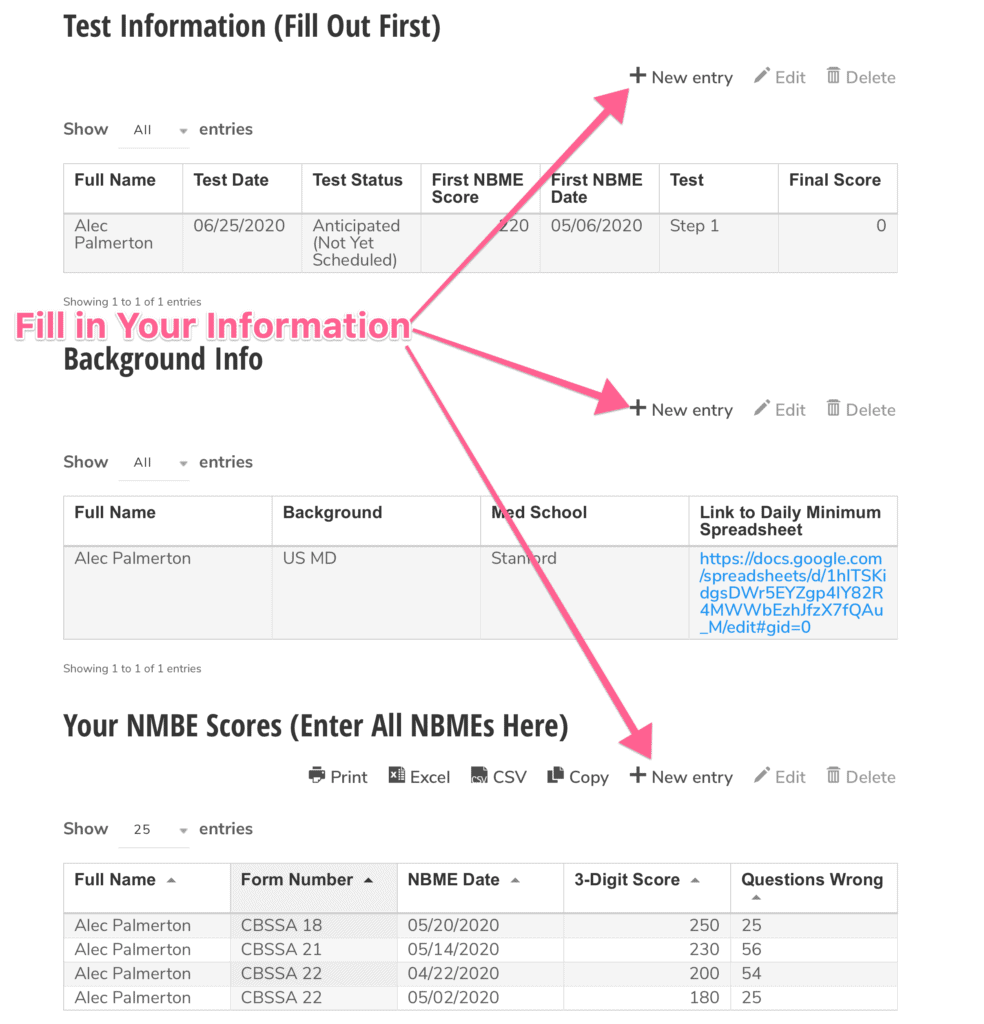

In the Progress Area, be sure to track your NBMEs. Here you can enter in your NBME scores and other important information.

You should enter your NBME information every single time you take a practice test!

While the causes of a score not improving are many, they tend to fall in one of three camps. Students whose scores are stagnating are either:

Rushing:

We’ve discussed rushing at length. Cramming/rushing leads people to take short-cuts. The first thing to go when taking short-cuts is study quality – mastering the material so you can understand and apply it.

Paradoxically, if you’re rushing because you don’t have enough time, we highly recommend delaying your test to the point that you no longer feel like you need to rush. In other words, let’s say you have a month until your test, but feel like you don’t have enough time. Consider delaying your test so that you have at least two, three, or even more months.

In our experience, most students know what they SHOULD be doing. They may know that they should master more, do their old Anki cards, or master question interpretation. However, all that goes out the window when time scarcity is introduced.

For more on the negative effects of rushing, read this.

Insufficient Minimums:

Another common reason for students’ scores to not increase is due to not doing enough minimums. If you’re doing all your Anki – but only doing 20 questions/day – you are unlikely to see a significant improvement in your score. Similarly, if you are doing adequate minimums, but only making 10 Anki cards/day, you likely aren’t building a strong enough foundation to improve your score significantly. This also applies to making cards – but making poor cards.

For more ideas if you’re struggling to do your daily minimums, read this.

Question Interpretation:

Insufficient minimums – or not making enough (quality) cards – would explain 80-90% of the reasons why students’ scores are not increasing. This is particularly true for students whose scores are below 220-230.

However, there is a small population of students who are doing their minimums and have a strong foundation yet see their NBMEs stagnate. Often, this is due to making “unforced errors.”

If your scores are stagnating above the 200s, particularly in the 220-230+ range, question interpretation likely plays a role. We recommend:

If you’re doing your minimums, investing the time to make enough high-quality cards, and mastering question interpretation, our expectation is your score should improve. However, what it takes to go from a 170 to 200 is different from what it takes to go from 220 to 240. Here are some general guidelines on what to focus on at different scores.

Below 200:

If your score is < 200, then building a strong foundation should be your primary focus. This includes doing your minimums, and in particular making excellent pathophysiologic chronology Anki cards.

200-230:

If your score is in the 200-230 range, your foundation is strong/improving. While you should continue to build your foundation, you should also start to focus on “mind-reading” – understanding the educational objective of each question.

To help you with “mind-reading,” we recommend doing this exercise. (Note: this exercise is intended for people in one-on-one tutoring with Dr. Palmerton. However, even if you are not doing one-on-one tutoring, you can still complete it on your own without the feedback of a one-on-one session)

230-250+:

If your score is above 230, much of your improvement will likely come from limiting unforced errors. Remember, improving your performance on easy questions can often lead to more improvement than getting every single hard question correct. This is especially true as your scores improve.

We recommend:

While scheduling a one-on-one session is useful generally, it is particularly useful for those who are trying to improve their scores from the 230-250+ range. If you’re interested in scheduling a one-on-one session with Dr. Palmerton, contact us at support@yousmle.com

I have forgotten much of what I learned over the past <2 years, especially most of the pathologies studied last term. What would be a systematic way of making sure I cover every single pathology I am supposed to know well before Step 1? For example, if I come across a Kaplan question on Chagas disease and if a contributing reason for my incorrect answer was because I knew some but not all details on Chagas, for example, that an affected individual can develop dilated cardiomyopathy, do I create knowledge card(s) that cover(s) all facts listed in First Aid pertaining to Chagas (because they are considered ‘high yield’)? Then, do I also make knowledge cards for dilated cardiomyopathy, obstructive cardiomyopathy, and restrictive cardiomyopathy because I don’t recall much on those either?

At the least, you should do this for 2-3 subjects per day. Your goal would be to learn all the FA-relevant material for Chagas.

Again, studying the cardiomyopathies would fall under the category of 2-3 subjects. I’d avoid trying to learn everything about everything – especially in the beginning where you are – because you’ll feel so overwhelmed which leads to stress, poor studying, and procrastination. Instead, I’d focus on mastering new information every day, and making sure you never forget the old.

To paraphrase Bill Gates, most people overestimate what they can study/learn in a month, but vastly underestimate what they can study/learn in 6-10 months. The best studying is studying you never have to do again. The worst studying is studying you have to repeat.

Pharmacology is a huge part of Step 1 and clinical practice. As such, students studying for either Step 1 or who are in clerkships should have a deep understanding of it. For Step 1 students in particular, pharmacology makes up 50+ points, so the difference of it being a strength of a weakness has a huge impact on your score.

To learn pharmacology principles, use the Yousmle Step 1 Deck, and supplement it with the information in the Pharmacology, Anesthesiology.

To master the actual drugs that make up the bulk of Step 1 pharmacology / clinical practice, use the Yousmle Pharmacology Deck.

They say the best time to plant a tree was 10 years ago, but the second best time is right now. The same is true of learning pharmacology. Ideally, we would have started at the beginning of each organ system that discussed those drugs. However, the second best time to start is right now!

Step 1 anatomy is one of the hardest subjects to study for. You may be tempted to do a book that includes anatomy in it, however, I haven’t found any that were particularly useful. (If you find one that IS useful, though, please let me know!).

Anatomy is hard because it often seems random what they test, and the content is pretty detailed. My best advice would be to do QBank questions, and master topics based on things you get wrong by referencing the First Aid related pages. If the information isn’t in First Aid, personally I’d probably just Google it for up to 5 minutes per topic. However, again, if you find a great Boards anatomy reference book, let us know.

Summary: QBank questions + First Aid-related mastery.

Another fact-heavy subject, like pharmacology and anatomy, is microbiology. My recommended approach is similar – you should use questions as a means of learning/surfacing the things you are weakest on, and address those weaknesses using First Aid.

Many students ask about Sketchy Micro. Mnemonics are, at best, “low” utility. They’re not useless – and can help you remember random facts. However, the question shouldn’t be, “can this help me?” Rather, ask, “what would the BEST use of time be?” (For more on evidence-based study techniques, see this article.)

If I were in my dedicated study, I wouldn’t bother with Sketchy, not because there isn’t useful information in it (there is). Rather, it’s because the most effective way to learn AND USE important facts is to apply them in context, in actual vignettes, rather than watch videos, memorize them, and then do questions afterward only to realize you didn’t quite understand those random mnemonics in the first place.

As a general observation, mnemonics are better than the placebo, but not by that much. That is at least the conclusion from a variety of reviews, including the one I cite here.

It is through that lens that I view Sketchy. Is doing a mnemonic to memorize which bugs are Gram + helpful? Certainly. Does that mean you should turn ALL of medicine into mnemonics? No.

Because mnemonics are better than nothing, but not the most effective learning technique, I would reserve them for places where you CANNOT make connections/find the underlying concept. Micro, while there are many concepts, still has a lot of memorization, so if there was ONE place I would use Sketchy, it would be microbiology. Other than that, I generally would not recommend using Sketchy.

There are two approaches to dealing with management questions. The first, which is practiced by most students is: memorize all of the details of management.

The second approach, which I advocate, is to focus on management principles. Specifically, whenever you make a stand-alone management question, you should ask two questions:

I emphasize the second point because it is the one people most likely overlook. The punch-line is that the more severe the condition, the more invasive the management. The less severe the condition, the less invasive the management. You can avoid tedious memorization of many details by recognizing this clinical principle. As a bonus, the “higher severity means more invasive management” principle is also true in real clinical practice.

Let’s take an example with acute diverticulitis. Let’s say our patient is this:

56-year-old male with chronic constipation has acute diverticulitis, is drowsy/confused, with abdominal guarding, and has a HR of 110/min and BP of 100/60 mmHg after 2L IV normal saline. What is the next appropriate step in management?

Most people have memorized that the appropriate management is antibiotics, IV fluids, and NPO. However, that will not always be the case, just like it is not the case for the above patient. The fact that appropriate management varies between question confuses students who then think, “but I don’t understand! The UWorld question just told me one thing, now another question is telling me another!”

Quite confusing to the student, however, it doesn’t need to be. It is because you are overlooking the disease severity.

In the above example, the classic management is wrong. Why? Because it ignores the illness severity.

If we tweak our vignette, however, the appropriate management changes, as well to reflect the illness severity:

56-year-old male with chronic constipation has acute diverticulitis, is alert and oriented, with abdominal guarding, and has a HR of 90/min and BP of 130/90 mmHg prior to IV hydration. What is the next appropriate step in management?

In this case, the appropriate stand-alone question would be something like: “what is the management of mild acute diverticulitis?” In this case, the management would be the classic, “NPO, IV fluids, and antibiotics.”

Often, you’ll find that most of the management options are appropriate for a given diagnosis. So they might list, angioplasty, stent, bypass, or exercise for someone who has peripheral vascular disease. It’s only by recognizing that it is MILD peripheral vascular disease that you can rule out all of the more invasive options (angioplasty, stent, bypass) and choose the appropriate management (exercise).

So to summarize: when constructing a stand-alone question for management questions, you should ask:

Then, based on the severity, choose the appropriate level of invasiveness. The more severe, the more invasive, and the less severe, the less invasive management.

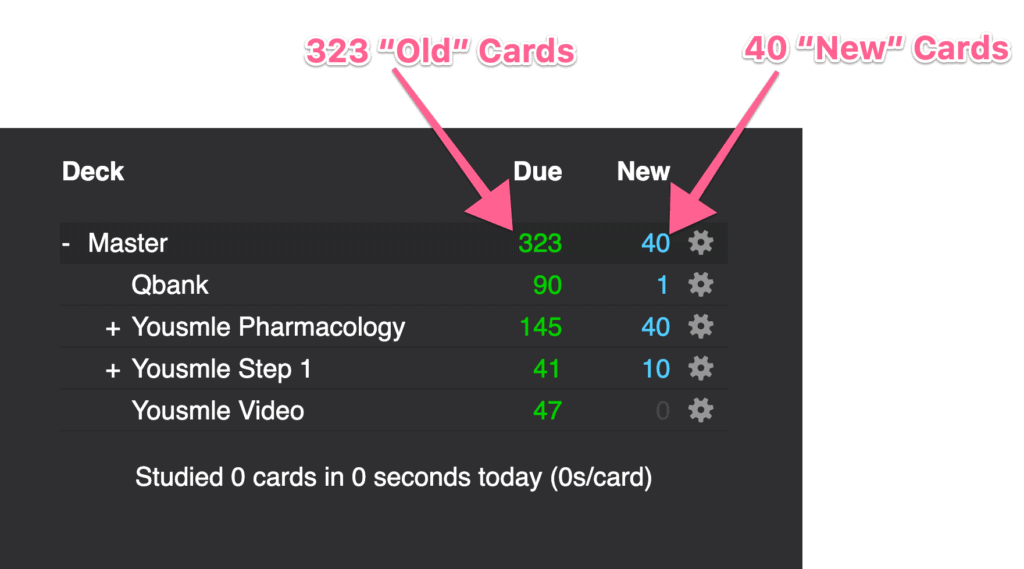

An “Old” card is one that you’ve reviewed before, and that the program is showing you again so you don’t forget it. It is the green number (“Due”) in your daily Anki reviews. You should review ALL old cards every day, so that you don’t forget the things you’ve learned / reviewed previously on Anki.

A “New” card is one that you haven’t reviewed before. It is the blue number in your reviews.

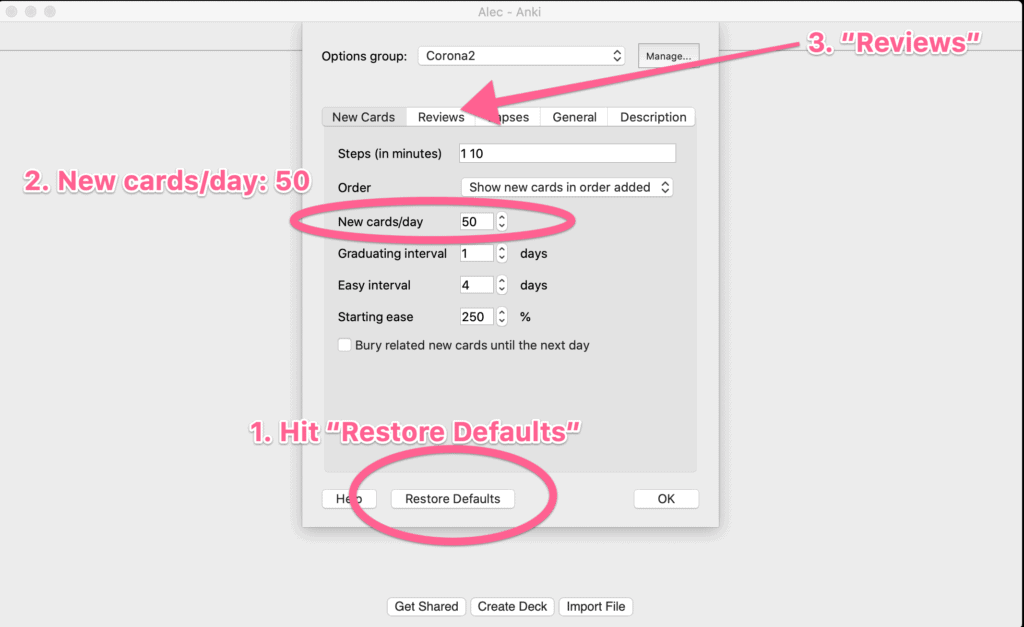

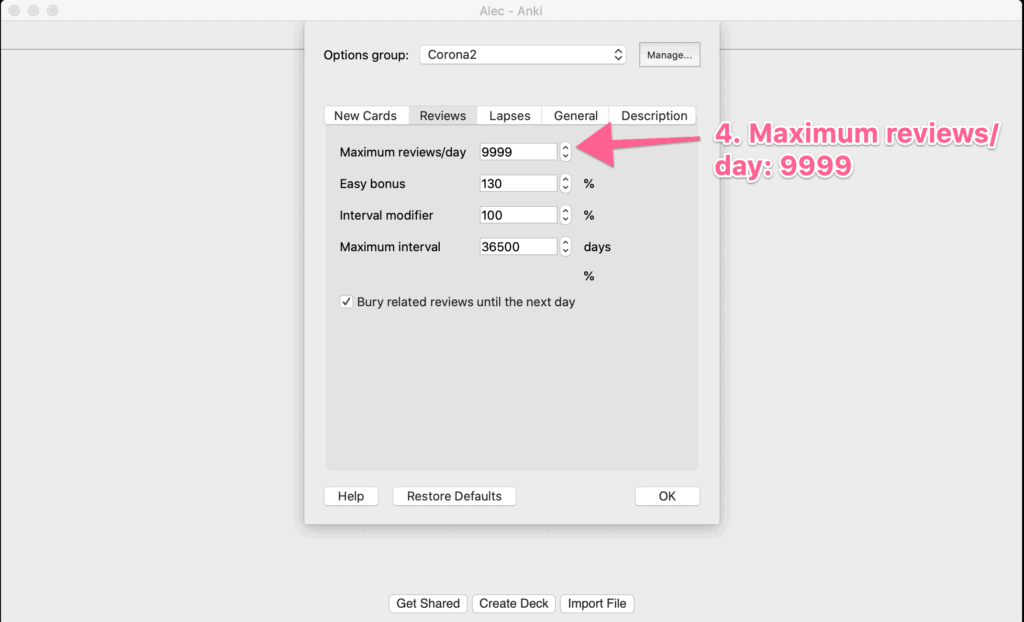

Generally, you should stick with the default settings for Anki. To be safe, hit “Restore Defaults” first, then change to these settings:

There is a difference between how many cards you make and how many cards you do. You can make 100 cards in a day, but you may only review 50 of those new cards (never do more than 50 new cards in a day; always do all old cards).

In an ideal world, you would limit yourself to making no more than 20-50 new cards/day on subjects you study, although this number will depend on how much time you have to study. For example, if you’re in:

The reason to limit the number of new cards you make is that you could make cards endlessly (and most people who start out do this). The reason? You think this random fact *MIGHT* be useful in the future, and so you make a card. The problem with this make-anything attitude is that you will drown in Anki and minimally-useful cards will overwhelm the few useful cards you have.

Initially, you should try and DO more Yousmle cards than your own, largely because it will:

Start with 60-80% of the new cards you do/day be Yousmle cards, including from the Step 1/Step 2 CK/pharmacology decks (depending on what exam you’re preparing for) and the Online Course. The remainder will be cards you make on your own.

Once you’ve done more of the Yousmle cards/feel comfortable making your own cards, you can increase this number, however, at least in the beginning, the majority of new cards you do should be from the Yousmle Decks or the Online Course.

Pre-made decks like Anking focus heavily on memorization, which might not be as effective for USMLE-style questions that require understanding and application of information. While these decks contain valuable information, they are often more about memorizing facts, making them less efficient.

Our Advice:

Deciding whether to continue using Anking involves weighing its benefits against its drawbacks. Consider the usefulness of the information versus the inefficiency of memorization-heavy study.

If you choose to stick with Anking, we recommend editing the cards to make them more applicable and connected to what you need to know. However, many students find it beneficial to create their own decks using the style they learn in the Yousmle program. Learning and understanding the material first, then using Anki for retention, often proves more effective than relying on pre-made decks for learning. Ultimately, the choice is yours.

The Yousmle Step 1, Step 2 CK, and Pharmacology decks are separate from the Online Course. They are highly recommended, and the cards in them are virtually all different from what is covered in the Course.

The best way to use them is to study them subject-wise with the Course subject you are studying. For example, if you are starting with cardiology, I’d recommend doing the Step 1 cardiology, Pharmacology cardiology and/or the Medicine (Step 2 CK deck) cards.

You will likely finish the Yousmle cards BEFORE you get through a particular section. That is desirable. Remember, while doing the cardiology Online Course section, you should also be doing cardiology QBank questions. For these QBank questions, you should be making your own cards, which you can do along with the pre-made cardiology cards.

The mix of cards you do each day might look like this (note that you should NOT exceed 50 new cards/day, to avoid being overwhelmed with old cards later):

You should always do your old cards. Always. However, if you don’t (and we’ve all been there at least once), and they build up, what do you do?

The longer you wait – and the longer the cards pass beyond when they should be reviewed – the more you’ll get wrong, and the longer it will take. Thus, the key is to catch up as quickly as possible.

I recommend setting your old cards due/day to 200, for psychological reasons. Then, once you’ve completed the 200 cards, increase the amount due to 300/day. You should see only 100 cards due now since you’ve already done 200. Psychologically, it is much easier to do 100-200 old cards than to see 1000+.

To catch up, stop doing new cards, and QBank questions. It may take you up to a week to catch up, but it is the cost of catching up. This is also a great reminder to not try and do more QBank questions/new cards at the expense of your old cards. In the short-term, you will see a (brief) increase in the number of QBank questions/new cards. However, in the long-term, you will do less of each, since old reviews will become a huge drag on your time.

For the most part, I don’t recommend resetting your cards. You’ll end up doing the same cards as you did before, but with each interval reset, it will take you longer. As an example, I was ~2000 cards behind at one point in residency. Rather than resetting my cards, I followed the plan outlined above – I simply set my old cards to 200 a day, and eventually, I caught up. In fact, I caught up much faster than predicted, since psychologically, going from 200 to 0 felt so good that I’d do an extra 100, 200, or even more cards that day.

Had I reset my 20,000+ cards, it would have taken me at least five YEARS to get back to the same point, if not more. Instead, it took me less than a few weeks.

There is, however, one situation in which you might consider resetting your cards. That is when you truly have forgotten most of the information in each card. How do you know? Each card feels unfamiliar, and you hit “again” more than 30-40% of the time and/or it takes you longer than 1.5 hours to do 100 “old” cards.

If each old card feels like your first time, you might as well bite the bullet and reset your cards. That way, you can have a fresh start, and feel less overwhelmed.

If you want to reset your deck, see my tutorial here.

There is a new way to add audio pronunciations to your Anki cards. You can go to this site, and find the term you need, and download it.

From there, you can add it to your Anki card:

Select File:

Shout out to Paula for the tip!!

You can find an article here on the website on how to force particular cards into your reviews for that day so that you can choose which new cards you study, rather than let the program decide for you.

Many of you know that I love reading, especially books that help me to adopt new perspectives. After receiving multiple requests for book recommendations, I figured I’d share some here.

Off the top of my head, my top recommended books for most med students:

Honorable Mentions:

Post questions to the Discord channel #yousmle-support-questions and we will do our best to respond promptly and update the FAQ.