NOTE: this assignment is most helpful if you have first mastered the Interactive Anki Accelerator exercise. If you have not done the Accelerator, do so first, then come back to this assignment.

There are 3 major steps to mastering question interpretation:

If you’re on this assignment, you already should be making excellent pathophysiologic chronology cards, so more of your interpretations become automatic. If you haven’t completed the first assignment, please do so here.

If you want a reminder of how to do this, see the videos here and here.

Table of Contents

Next, I want to help you hone your ability to understand what the questions are asking more, so you can get more questions right on the topics you have knowledge for.

That’s the holy grail of studying: getting more questions right without having to learn more.

Simply put, every question has a purpose or “educational objective.” The NBME, writers of the USMLEs/shelf exams, make this very clear.

However, when you read the question, it’s not immediately clear what that objective is. We get so mixed up by tiny details. Exactly how many years did he smoke? How many days was it of epigastric pain? Was there nausea AND vomiting, or just nausea?

Rarely do questions hinge on these small details. Rather, the vignettes are meant to illustrate broad concepts.

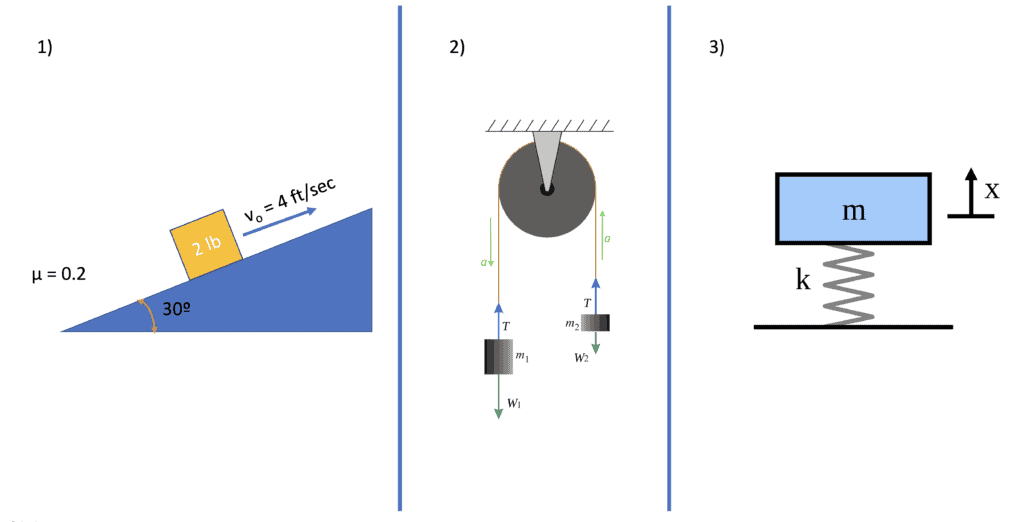

One of my favorite education experiments goes something like this. Two groups of physics students – beginners and grad-level – were shown standard physics problems. Things like:

They were then asked to categorize the problems.

Guess who did better? Obviously, the grad students. However, what was interesting was the differences observed.

Beginners: focused on superficial differences

Experts: focused on the principles underlying the problems

1., 2., + 3. They are all conservation of energy problems

In other words, the experts were able to abstract the key concepts, and apply them broadly. To them, it wasn’t three distinct problems. Rather, it was simply one concept, applied in three different ways.

Another thing that stood out was that beginners were more easily distracted by superficial similarities. The same diagram may be used for two different problems testing two separate concepts.

Beginners were more likely to categorize these problems as the same, because of their superficial similarities. Experts were able to look past the superficial similarities and see that the core concepts were different.

The parallel with the USMLEs is striking. The “beginner” mindset is to look at each problem and get stuck with the details. In contrast, the experts are looking to identify the broad concepts that each question is asking.

An excellent example comes from Step 2 CK. Many people assume that they need to study subject-specific material, like pediatrics, or Ob-Gyn. While there is certainly some subject-specific material you will need to cover, it is a lot less than most people assume.

Consider four different scenarios:

Technically, each of these comes from a different section of Step 2 CK. However, fundamentally, they are all the exact same concept: shock. Each of these represents a different form of shock. One concept, four different applications.

Or consider the following histopathologic descriptions of various diseases:

The beginner will see all these as separate processes, each of which needs to be memorized. The master will see these all as the SAME process (chronic inflammation → fibrosis +/- dystrophic calcification).

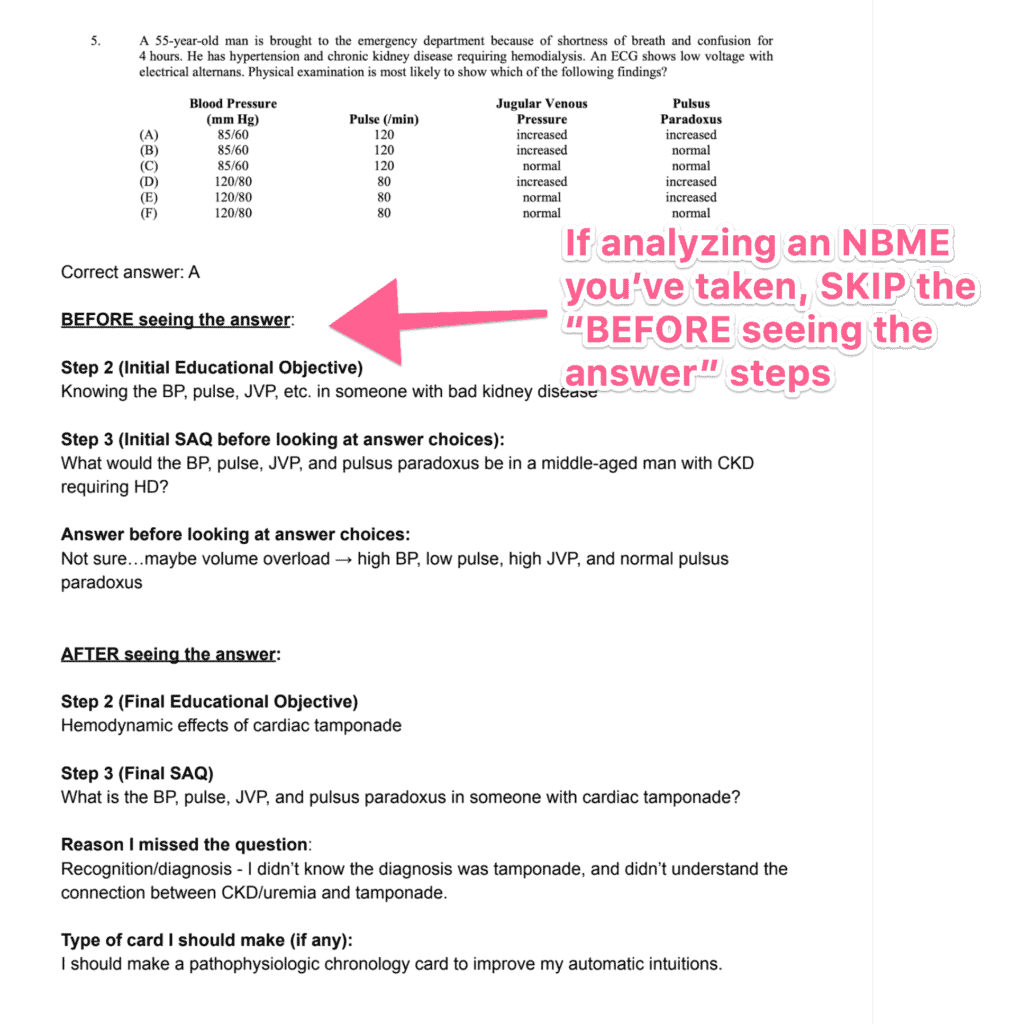

To that end, make a Google Doc with screenshots of 3-5 QBank questions, along with your SAQs / answer / revised SAQs. (Explanation below). If you are currently doing one-on-one tutoring with me, please share it with me, with edit access so I can give feedback if appropriate.

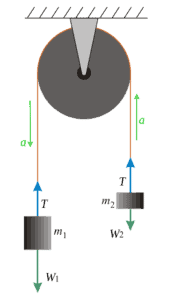

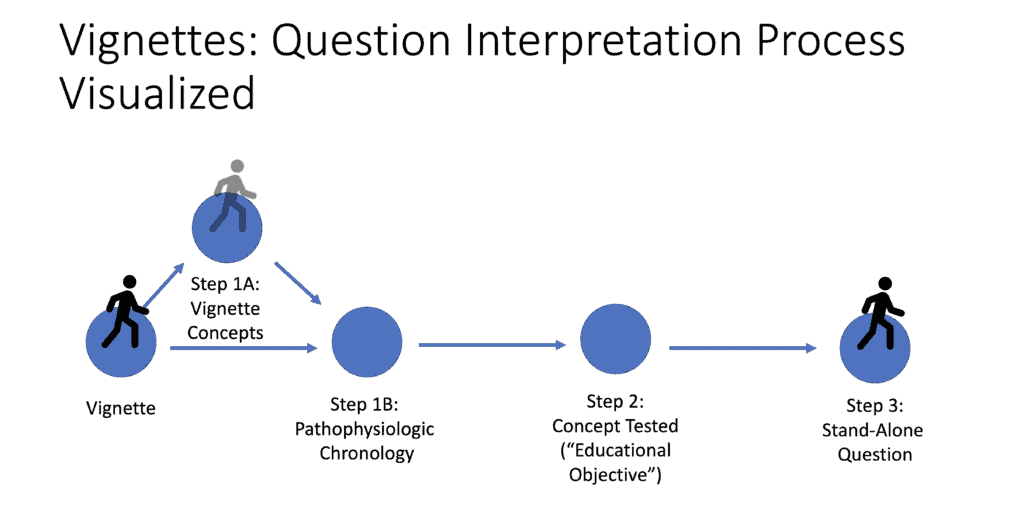

As a reminder, here are the steps for question interpretation of vignettes:

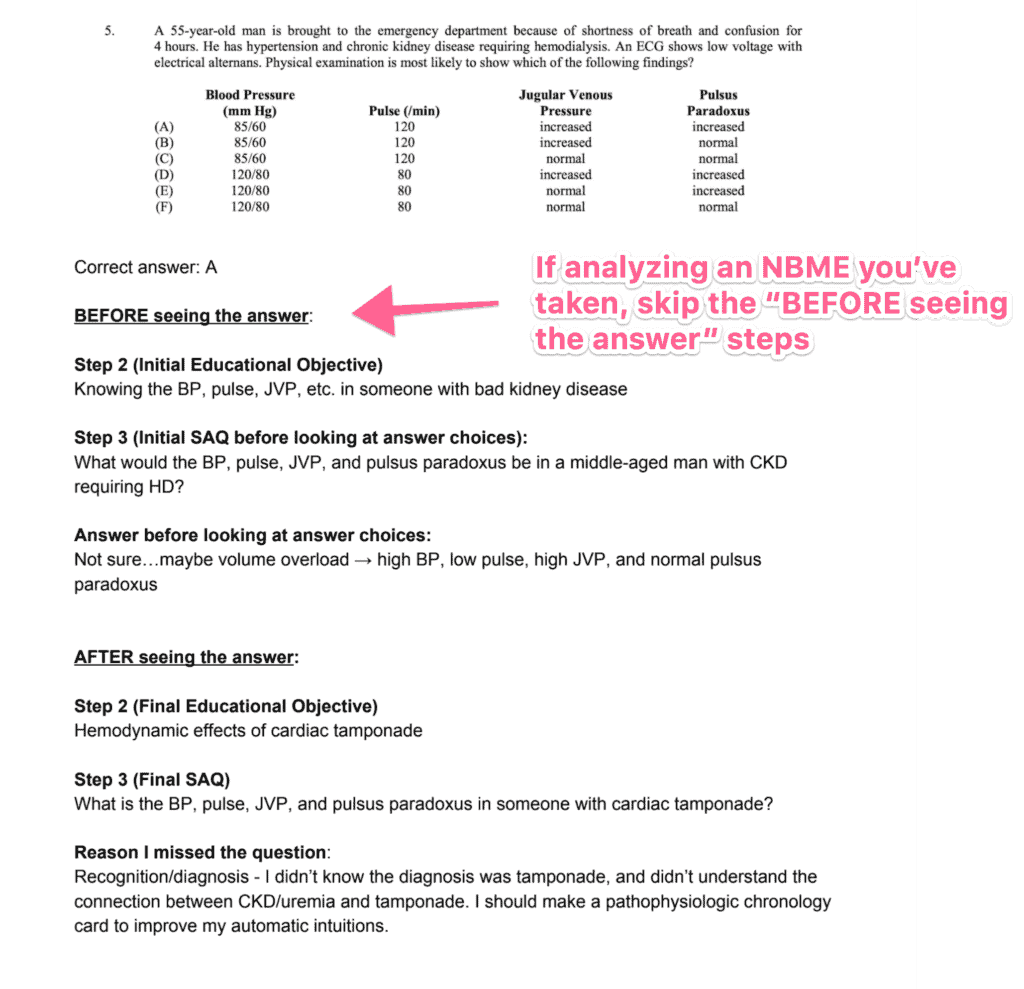

We already have an assignment for Step 1A/1B, so today, we will focus on Step 2 and Step 3.

BEFORE answering each question, I want you to (NOTE: SKIP this is you are analyzing an NBME you’ve taken):

AFTER answering each question:

The goal is for you to keep improving your “mind-reading” of the question writer. Initially, your pre- and post-education objectives and SAQs will likely vary, maybe even a lot! But over time, with practice, you can train yourself to spot the concepts they want you to learn about.

We may have talked about this psych/education experiment, where they had grad students and beginner physics students look at physics problems and try and figure out what “category” each belonged to. The grad students did better, of course. However, it was HOW they did better that was so fascinating. The beginner physics students tended to get bogged down by superficial details (“this is a question about a ball being dropped, and they’re asking about the speed”) whereas the grad students more easily recognized the underlying CONCEPTS (“oh, this is just another question about conservation of energy”).

An example for medical school would be a question about a burn patient. Let’s say the patient was just in a house fire, and has 60% body surface area (BSA) burns. They are tachycardic, hypotensive, and tachypneic. Their sodium is 140 mEq/L, K+ is 4.5 mEq/L, and serum glucose is 80 mg/dL. They ask you, “what fluid would be most appropriate to administer in the management of this patient?”

What would your SAQ be? Try it, write it out first before you look at mine.

The “beginner” SAQ would be this: “what fluids would you give to a hypotensive, tachycardic patient that has a glucose of 80 mg/dL?”

The “advanced” SAQ would be this: “what fluids would you give for volume repletion?”

Notice the difference! The first question, I have almost no chance of getting. How could I possibly know what specific fluids I’m supposed to give in every situation. No wonder people think that the USMLEs are all about memorizing details!

But the “advanced” question is simple. For volume repletion, you probably knew that you give some sort of isotonic fluid, e.g., normal saline or lactated ringers. So simple!

Learning one concept and learning how to apply it broadly will save you tons of time – and give you a higher score/better patient care skills – than treating everything as an individual detail to be memorized. The stand-alone question is a related – and crucial – skill; while there are lots of different details they can use in each question, there are many fewer core CONCEPTS that they can test you on. The more you can learn what CONCEPTS they are emphasizing (rather than focusing on superficial details) the better you’ll be able to “read the mind” of the test-writers.

Let me know what questions you have!

I want to help you to develop a strong foundation. To that end, I have a homework assignment for you:

To do this, please include:

Here’s an example of what it might look like:

Here are some common mistakes I’ve noticed. Learning these can help you to accelerate your own studying.

I know you have been thinking of pathophysiologic chronologies. However, this is not an exercise in pathophysiologic chronologies, per se. As such, please don’t include PCs in the assignment:

SAQ: In a female with menopause and sudden light spotting , best next step ?

REVISED SAQ: PPC: 57 FEMALE → ACTIVE LIFE NO MEDICAL CONDITIONS → MENOPAUSE AT 53 → NL BMI, NL MAMMOGRAPHY, PAP TEST → SUDDEN SPOTTING → what to do in a postmenopausal female with bleeding?

Remember, the point of a stand-alone question is that it should:

In other words, someone should be able to skip the vignette, look only at your SAQ, and know exactly what the educational objective was.

Make a Google Doc and share the link with me. IMPORTANT: Please share with me via the Homework Assignment table on your progress page: https://course.yousmle.com/progress

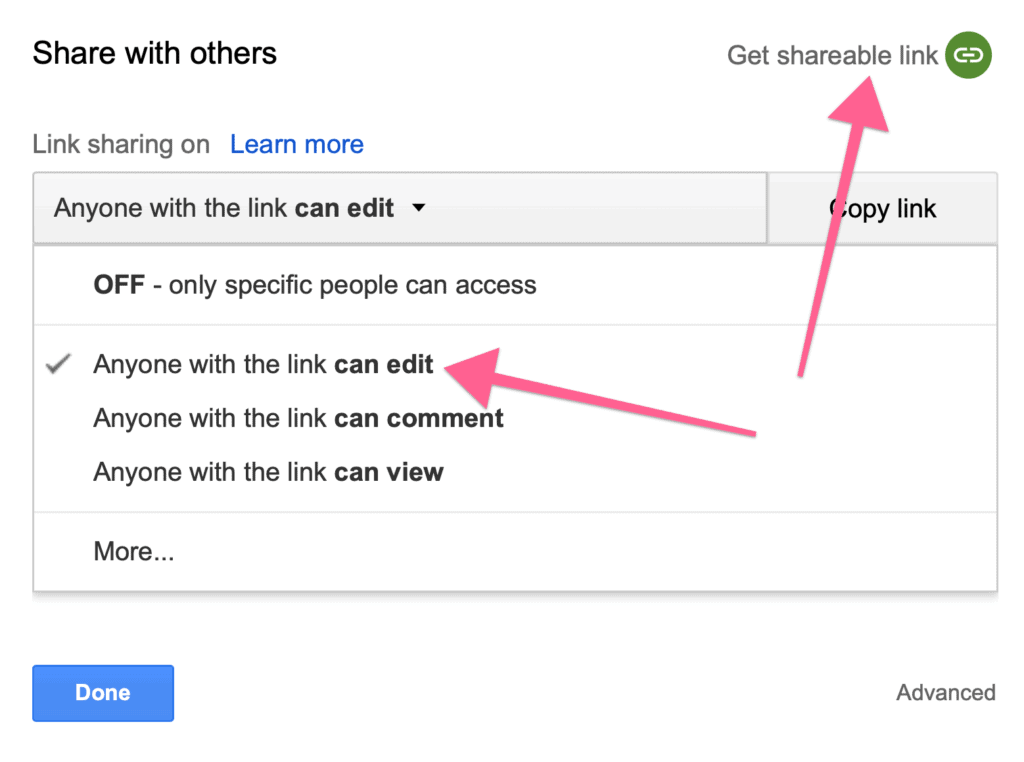

Be sure to give me edit access so BOTH of us can type into the document. Read about how to do this here.

Please share the document with me, and allow me to edit it

Please share the document with me, and allow me to edit it

IMPORTANT: Please share with me via the Homework Assignment table on your progress page: https://course.yousmle.com/progress

References: